[I meant to post this yonks ago…]

Imagine beginning your day with root canal surgery. Surely you would think the day could only improve from there. But not so for Alan Johnston, the BBC correspondent based in Gaza, the only western journalist living in the dangerous Gaza Strip, who on 12 March this year was due to return home 16 days later after a three-year stint. Alan left the calmer grounds of Jerusalem that morning where he’d had undoubtedly painful dental surgery, and returned home to Gaza, reporting for work. After he left there, his car was overtaken and he was kidnapped by what transpired to be the dreaded Army of Islam, and whereas most kidnappings in the area ended with the hostage being released in a week or so, this kidnapping was to be different.

The recent BBC Panorama special Kidnapped: the Alan Johnston Story was absolutely gripping despite the weak arty ploys of manipulative, nauseating camera-jostling to convey the chaos of the kidnap that we must be too stupid to imagine; the staged feel of the stark interview space: an empty converted warehouse; screeching ravens attempting to lend a disturbing Poe uneasiness to proceedings; and distracting cryptic glimpses of a woman in a field. Most absurd was bizarrely unveiling the latter’s significance—that Keats’ reference to the Biblical homesick Ruth “amid the alien corn” was on Alan’s mind during his captivity--as though that revelation was the exciting denouement of the story, when that honour went to the joyful, heart-warming moment four months after he was taken when Alan and his friend Fayed Abu Shamalah laid eyes on each other and knew Alan was finally free.

The comfortingly calm Alan is an amazing, engaging raconteur whose tale needs none of these gimmicks, and I look forward to his future work from somewhere safer if that would not bore him. Whereas the nauseating camerawork turned my telly into radio as I was forced to look away, by contrast I was captivated by clips of the impressive (and surprisingly tender, given his job) BBC Head of Safety, Paul Greeves, and Alan’s delightful editor, Simon Wilson (surely a gentle giant?) speaking of their concerns and astounding work attempting to secure his release, as well as being touched by Alan’s magnificent parents, clearly the source of his superb grounding, courage and intelligence. Few films could have such a happy ending as Alan wandering free through the bright Argyll countryside, although our glee was tempered with the harrowing, important reminder that British hostages remain missing in Baghdad, and I hope their stories’ endings are as happy soon.

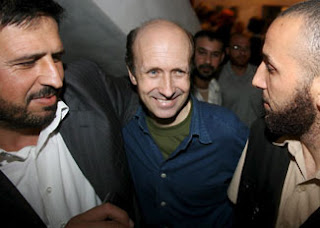

I recorded the programme and if DVDs could be worn out by repetitive viewing of a particular chapter, I would have destroyed it by now from watching umpteen times the moment Alan is describing how he is taken out to an unknown fate by his kidnappers, who had just beaten him and held a  Kalashnikov to his head, then dumped him in an alley at the foot of a row of armed men, and like an animal with no control over his own situation, he had no idea what that meant and wondered whether the men who were taking him around the corner were a new gang who had taken charge of him…..until he caught sight in a tent in a garden of his friend and colleague Fayed Abu Shamalah (Fayed is pictured on the left of the picture with Alan when he was freed).

Kalashnikov to his head, then dumped him in an alley at the foot of a row of armed men, and like an animal with no control over his own situation, he had no idea what that meant and wondered whether the men who were taking him around the corner were a new gang who had taken charge of him…..until he caught sight in a tent in a garden of his friend and colleague Fayed Abu Shamalah (Fayed is pictured on the left of the picture with Alan when he was freed).

Then, the programme switches to Fayed’s point of view, who sweetly describes trying to comfort Alan and drum home that he was free, grabbing hold of him and not letting go for hours, and then we are shown the footage of Alan, with his friend Fayed’s arm safely wrapped around him, guiding him through the chaotic crowds jostling him in a happy madness. Then we get to see his parents, all smiles, speaking of hearing Alan on the phone right after that, and the world is a better place. I well up ever time I watch this and it might replace Singing in the Rain and Father Ted as tried-and-true medicine for cheering me up when things are horrid.

Some things in particular that stick in my mind from this programme are:-

- The amazing warmth and professional skill at dealing with this unusual situation--implementing a protocol written by Alan--conveyed by Greeves and Wilson (Director-General Mark Thompson came across as less caring and more business-focused but I sense that's an unfair depiction)

- His absolutely precious father describing how nervous he was addressing the packed press briefing and television cameras but that he focused on speaking directly to his son, who incredibly saw the plea and was comforted by seeing his parents strong and dignified

- Wilson describing moving into Alan’s flat in Gaza after Alan had been taken, which must have been terrifying for him and his family given the fate of the only other western journalist in Gaza, and his comment that the existing provisions suggested that Alan lived off chocolate and green beans (perhaps because his pre-root-canal mouth could take nothing more?)

- Greeves’ description of the horror of waiting for the slow download of the video posted to the web by the terrorists who had threatened to kill Alan, and dreading clicking ‘play’ for fear of what it would reveal

- My being reminded of the worldwide peaceful demonstrations against his kidnapping

- The mix-up that in other circumstances would have been hilarious, when his colleagues tried to ascertain whether Alan was still alive by asking the kidnappers to get from him the name of his childhood cat in South Africa, and learning that a language mix-up meant Alan was asked ‘What is the national cat of South Africa?’ and picturing Alan trying to think of an answer in case his life depended on it

- Wondering why his kidnappers gave him a radio that received the BBC World Service--perhaps it was to keep him quiet like sticking a child in front of television--and did they know that he was Scottish when showing him part of the Scotland–France football match?

- The dilemma of the Foreign Office in deciding whether to work with Hamas, which they’d previously labelled as a terrorist organisation, but which were gaining control of Gaza and thus could provide the key to rescuing Alan

- The horror Alan must have felt when hearing the incorrect radio report of his death, which he now jokes Twain -style had been exaggerated, but he did worry of the impact on his parents, and I wonder if he realised a search might stop if he were thought to be dead.

- I worry that Alan’s underplaying the trauma he must be going through, although he is clearly very grounded, stems from his modesty and determination not to complain too much when he may feel that others, such as the Beirut hostages, suffered worse fates, and I worry that he’ll let undeserved guilt creep in—but he had no freedom and a lot of fear

- Alan used to dream of being out of that room and wake to the horrors of finding he was still there; now he is out of that room and has nightmares that he is still there and must wake screaming—though fortunately finds that he’s free and I hope improves

- I wonder what guarantee of safe return the captors had when clearly they crossed several Hamas checkpoints to deliver Alan and had threatened to shoot him if the guards didn’t back off, so how would they expect, without Alan as security on the way back, to escape with their lives and freedom? It seems a surprising risk.

- I wondered what Alan thought of being taken to pose and dine with Ismail Haniya, the Hamas leader in Gaza, given that some viewed Hamas as terrorists, but I suppose he was grateful to be freed, and Hamas contributed to his being free

- It must have been awful for a journalist to miss the biggest story (next to his own) happening on his patch when Hamas took control of Gaza, and maddening for any to be trapped in an empty room for so long with so many thoughts and no facility to write them down; no wonder he spoke so fluently upon his release

- Alan seems to have protected himself with a remarkable self-awareness, fighting off feelings of despair as though he borrowed a weapon from his captives and used it to shoot down any depression-inducing thoughts, but I hope he treads carefully for some time so those thoughts don’t rear up and overwhelm him.

What is upsetting are some of the cold remarks made with prejudice and hindsight scattered across the web. There are accusations that the dear Fayed Abu Shamalah was linked to Hamas, which the BBC absolutely refutes, saying the rally he was accused of attending was a press briefing with numerous journalists who would have reported any such outrageous irregularities. In any case, any good reporter would foster contacts with all sides. There are also many unjust criticisms of or plain unkind comments about Alan and those who worked to free him, clearly made by people with firm political views who are too focused on their prejudices to applaud the fact that a man criminally stolen from the street is now free, which is all that should matter, regardless of one’s political views.

I feel annoyed when people ask why didn’t he try to escape—to what? They weren’t there, and he had no idea where he was, other than that he was surrounded by people who loathed what he represented and had an arsenal, in a bad part of a bad town, and he might have escaped from one room only to be shot in another, and if he actually made it to the street, the only westerner wandering lost, nearly blind without his contacts, would hardly get far before being recaptured or worse. He played it safe rather than being stupid, thank goodness.

There are also the inevitable cruel comments that emerge whenever anyone addresses the inevitable media onslaught following such a situation, accusing him of overkill by now granting so many interviews and even cashing in on his ordeal by publishing a book on the experience. So what? He didn’t arrange his kidnapping for eventual profit and celebrity! It must be cathartic for him to write—he’s a journalist after all, and was for four months without any means of jotting down his myriad thoughts, which were all he had to occupy him, so no wonder he has so much to say now. It’s all part of his recovery and he seems keen to return to obscurity. I feel he’s doing his duty now, almost like the royals granting photo calls on the condition that the media leave them alone for the rest of their ski trip. I hope he’s not weary of repeating the account of what happened, and that his future in London, if he works for his beloved World Service, would not be too dull for him, as he’s usually based somewhere dangerous.

It is bad enough that the Beeb plans to cut down on factual programming, like the World Service, a service of which Alan spoke after his release joyfully, calmly and fluently about his ordeal at his press conference (which can be seen on YouTube), as no doubt he had been imagining and dying to do for four months, full of jokes about having got a haircut to remove that ‘just kidnapped look’ and recommending the BBC World Service to anyone who found themselves kidnapped. I’m sure the World Service is a comfort to many people around the world and I worry about the threatened BBC cuts to factual programming, when there is so much dross and so many overpaid presenters that could be pruned out instead.

Incidentally, anyone wishing to explore the ‘alien corn’ reference, it refers to Ruth following her mother-in-law Naomi to Bethlehem to become a gleaner in the fields after Ruth’s husband died (“Whither thou goest, I will go,” Ruth 1:16) and describes someone who is alone in a foreign land in alien surroundings. John Keats alluded to that in his famous Ode to a Nightingale poem, writing of the bird’s lovely song, “Perhaps the self-same song that found a path / Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home, / She stood in tears amid the alien corn''. The same poem contains the more well-known phrase, “Tender is the night.”

Alan is a truly impressive soul, and if he ever finds himself wandering through the City of London, I’d love to buy him a coffee—just as a humble congratulations and gratitude for daring to put his life in danger by reporting the truth to so many people who don’t care as much as they should that so many correspondents are doing that. It would have to be a big, expensive Starbucks coffee, obviously, and I would not make him talk about his kidnapping unless he wanted to; I’d be interested in learning about that cat in South Africa, his studies (as I also have a degree in journalism, but a wasted one) and walking in beautiful Argyll. He’s not Alan Johnston the Freed Captive, but an amazing, intelligent, soft-spoken, Decent Human Being and remarkable journalist. He seems like he’d be a joy to meet.

I also recommend downloading the podcast of Alan’s account of his ordeal on Radio 4’s From Our Own Correspondent, or reading it on the webpage.

No comments:

Post a Comment